The details of the forest reveal themselves sharply in winter. The edges of trees create dark patterns against a white background. Tracks are preserved in the brush of cold, new snow that coats the ice. Sounds carry with a clarity that interacts with the cold and the sky in ways unique to the season. I can hear the twitter of small birds in the distance. The sound of the city is all around as a backdrop. Still, there is a deep silence here, something very old.

What does it take to get to know a place; to really experience it in its variety of moods and possibilities? To begin, one must visit it at all times of the day and night and in all kinds of weather and in every season. The shifting interplay of water, light, and wind, the dynamics of the living world’s seasonal changes, the ever-changing perspective of the human being who brings his or her conscious eye to a place, all reveal a text of infinite complexity and deep mystery. And it is in this context that questions emerge, questions that form the basis of a lifetime of study.

I remember once on an improbable walk through these woods on a winter’s night. Improbable because who takes walks in a New York City park at night? The moon was full. The woods with their snowy blanket were brightly illuminated in shades of black and white and blue. The edges of space itself seemed to touch the treetops. The stars shown with a brilliance rarely seen in our city. I was stopped in my tracks at the sound of an owl’s hoot somewhere in the trees. This wilderness was my urban home.

Now, moving slowly across a downward gradient that slopes from south to north, I am amazed at how large this woodland is. I have viewed the Clove from the ridge top and walked through it on its principle pathways. But this walk off trail reveals intricate details: a wealth of understory plants and shrubs, centuries-old trees that tower above the forest floor, the tracks of birds large and small, a variety of seeds that have fallen on the snow, a dry stream bed that traverses the length of the Clove, the sound of the wind in the treetops, and a single human track of someone who came here before me.

And, perhaps most affecting of all, within these woods, as the daylight fades and the snow takes on the color of the sky, I notice that the bowl shape of this valley creates an impression of relative boundlessness. It is as if I am visiting a great forest much bigger than the actual size of the Clove. Could it be that the ridges that surround this place preserve its ecological character as well as a deep wildness?

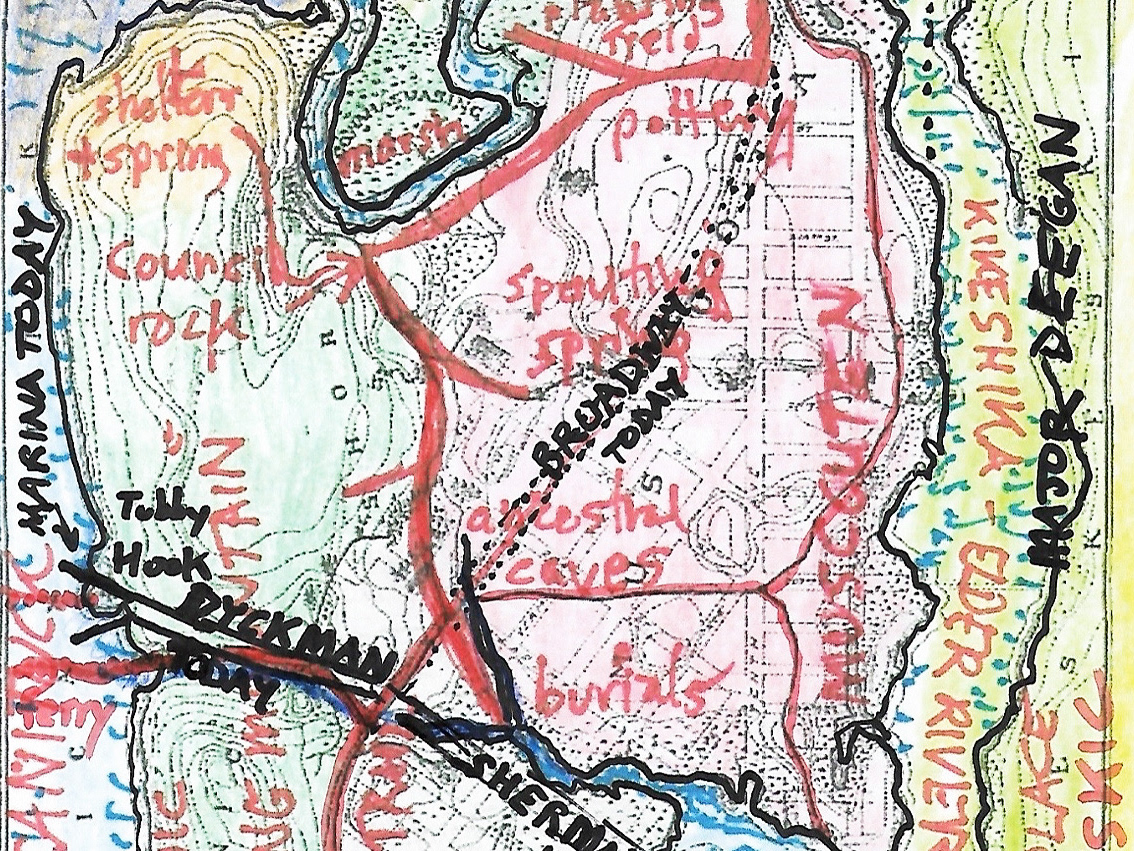

As I exit the forest onto one of the paths that crisscross it, I wonder at the problem of how to communicate something of the special nature of the Inwood Forest. Would my description take on the form of lists of species? The geological processes that formed this valley? The cultural history of the land beginning with the Native Americans who once called this place home? The important role green spaces like this play within urban ecosystems? Or, would it be a story of my long relationship with this place? The feeling of connection and inspiration time in this urban woodland engenders in myself and others? Surely, a complete cataloging of the Inwood Forest would include all of these things, and much more.

Photo by Marie Viljoen 66 Square Feet

Winter is coming to an end. In the Clove, white patches of hard packed snow are beginning to reveal the dry leaves, pieces of wood, stone, and earth beneath. The footprints of so many visitors are melting away. The spicebush already have fat buds waiting to burst open. The spring migration of birds will start soon. I will miss the quiet and mystery of winter but look forward now to the wonder of spring and the return of life to this woodland valley.